The Answer to What Question?

In pursuit of the questions and answers that shape our world.

“You take delight not in a city’s seven or seventy wonders, but in the answer it gives to a question of yours. Or the question it asks you, forcing you to answer, like Thebes through the mouth of the Sphinx.”

Imagine a dialogue between Marco Polo and the Chinese Emperor Kublai Khan, in which Polo vividly recounts the cities he discovered on his travels. This is the setting of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, the immersive book that inspired the title of this publication.

Eventually, he reveals a secret (spoilers!): “Every time I describe a city, I am saying something about Venice.” Though Polo recounts 55 different cities, they are, in reality, all fragmented reflections of his hometown.

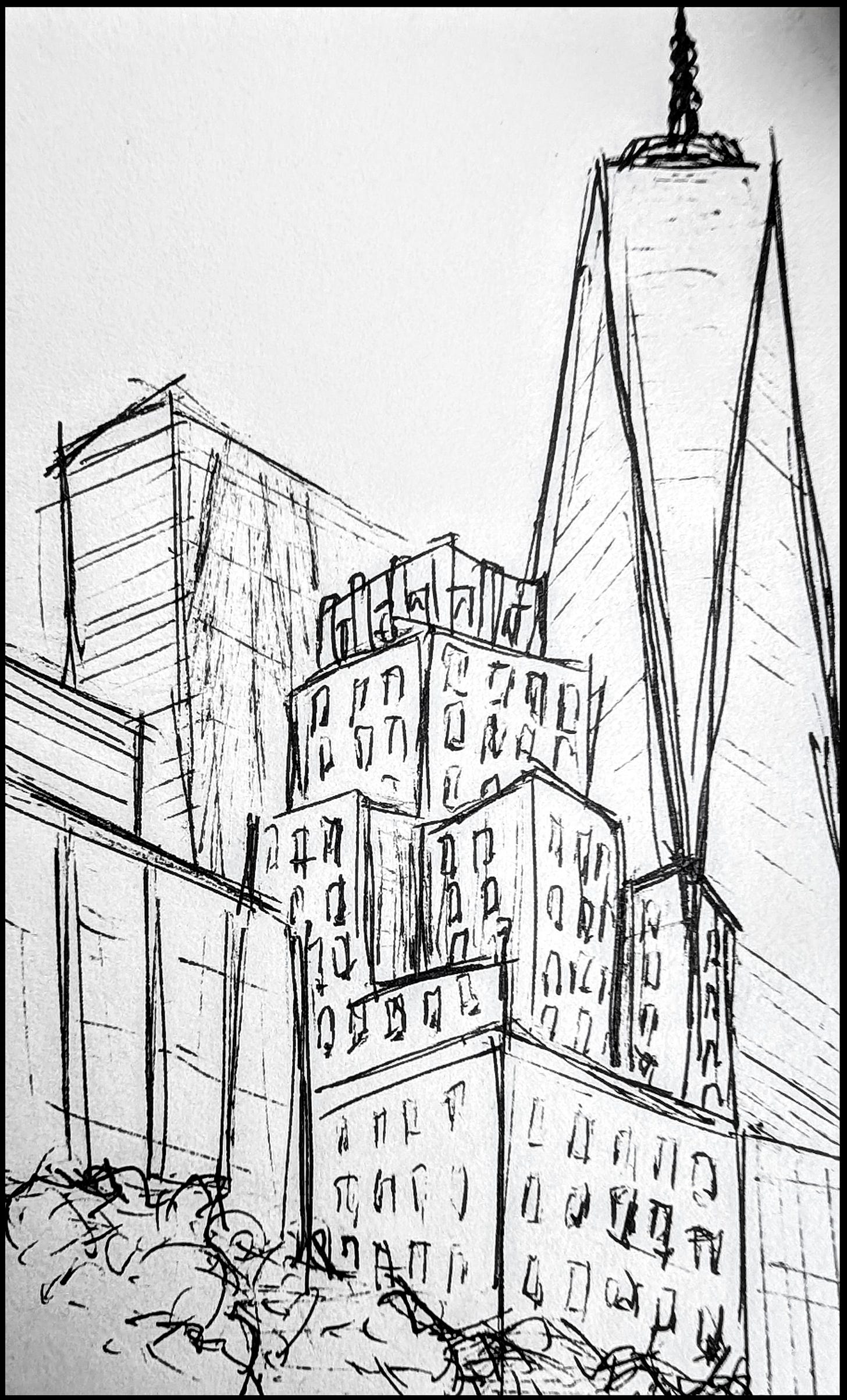

This idea reveals a profound truth about our cities—and more broadly, our institutions—they are invisible in their totality. Consider New York City. Even if you dedicated a lifetime to walking down every street, riding every subway, and working within every branch of government, you still wouldn’t have seen everything. And here's where it gets even more fascinating: human experience is beautifully peculiar. Two people could follow the exact same path, yet their individual perspectives would paint vastly different realities for each of them.

“Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful, and everything conceals something else.”

This publication will explore how the tangible elements of our cities and governments—policies, infrastructure, and more—shape, and are shaped by the intangible: desires and fears, quality of life, a sense of justice, and our collective capacity to flourish. We will move beyond the visible to the invisible layers of human experience that define them.

Our perception of cities and governments is undeniably subjective. However, I will strive to objectively write about what is, and why it is, in all of its inherent subjectivity. Only after seeking understanding will we (perhaps) move on to what ought to be.1 For it is vital to understand something before attempting to change it.2

I hope these sometimes interconnected, often winding threads of writing contribute to the weaving of a more complete tapestry of answers about our invisible cities.3 And that through this shared exploration, we may better understand the questions we ask, and the questions that are asked of us.

Thankful to have received this insight from Daniel of Maximum New York and The Algernon Project!

I’m reminded of G.K. Chesterton’s “reformer’s paradox”, introduced in The Thing (1929): Never tear down a fence until you understand why it was put up in the first place.

The imagery of weaving together threads is inspired by Niccolò Machiavelli in The Prince (1532): "The different types of principality I have mentioned will be the threads from which I will weave my account."